I recently attended the Pani Haq Samiti, or Right to Water Solidarity March with Yuva. The march was in celebration of the Bombay High Court’s recent judgment to provide 45 liters of water to all individuals living in slums regardless if they are legal or illegal slums. The State of Maharashtra considers illegal slums to be communities which were developed after the year 2000 as they are not regulated by the state. Prior to this policy reform, slums which were developed before 1995 were the only slums protected under the Maharastra Slum Areas (Improvement, Clearance, and Redevelopment) Act (Khan, 2014).

The Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM) had to develop a policy by the end of February regarding water supply to slums (Deshpande, 2014). During the Public Interest Litigation (PIL), the campaign Pani Haq Samiti demanded that all slums should receive water as it is inherent to life and part of Article 21 of the Constitution. The PIL was opposed by the MCGM and the state government because they believed it would condone the development of illegal slums and they also did not agree that it was unconstitutional to deny folks in the illegal slums water (Deshpande, 2014).

Nevertheless, the Bombay High Court amended the Maharashtra Slums Area Act of 1971 and included all slums, including those developed post 2000, to be protected and receive 45 liters of water per person per day (Khan, 2014). The Pani Haq Samiti March was certainly a day of celebration, but also a public display that people will continue to fight against inequitable policies and violations to their rights.

Furthermore, the march had historical significance. Exactly 86 years prior to this march, Dr. Baba Sahib Ambedkar led the Mahad Satyagrah in the exact location of the Pani Haq Samiti March. The Mahad Satyagrah was an initiative to fight for human rights which were being denied to the Dalit caste, a severely marginalized group in India. In 1923, the Bombay Council proposed a resolution to allow individuals belonging to the Dalit caste to collect water from public facilities, but it was denied by the Municipal Boards (Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, 2003.) The Satyagrah fought for the Dalit’s to be allowed to drink water from the public Chavdar tank which resulted in the Mahad Municipality passing the order, although it was not fully implemented (Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, 2003). On March 20, 1927, Dr. Ambedkar led thousands of Dalits to the Chevdar tank to collect water. This was strongly opposed by upper-caste Hindus who then added 108 pitchers of water to the tank to cleanse it after the Dalits used it (Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, 2003). After this circumstance, the order granting Dalits the use of the tank was eliminated by the Mahad Municipality, but after years of fighting for the right to water, the Dalits were granted access to the Chavdar Tank in 1936.

Dr. Ambedkar’s ashes are also kept at a temple in this location so it was really cool to visit it after the march! It was a very powerful experience for me to be a part of this for a lot of reasons. Learning about the Pani Haq Samiti campaign truly displayed the hard work, tenacity, and persistence of the workers in this organization. By demanding that access to water is a constitutional and human right, they had a profound role in changing the policy.

I also really enjoyed partaking in a protest in this culture, even though it was entirely in Hindi and I could not understand what was being said. It was very moving to be an observer. The historical significance of the fight for access to water also made the experience really special for me. There was a lot of excitement in the crowd and the protesters seemed to march with pride; their heads held high. The Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment (2003) stated that the Mahad Stayagrah March inspired hope in the Dalit protesters while also reminding them that change will not be accomplished without challenge. I am confident that this too holds true today for the marginalized individuals living in the slums. There is such a disconnect from the policy makers and those who are marginalized. The current ruling political party in India, including the state of Maharashtra, is the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) or the Indian People’s Party. It is a right-wing party whose philosophy is grounded in integral humanism, an economic development model which is human-centered and opposed to capitalism and socialism (Wikipedia, 2015). Here is an excerpt from the BJP regarding their development plan:

“When a political party talks of development, it often talks of roads, ports, GDP growth, stock markets, agriculture, exports and international TRADE , among other issues. To the BJP, however, development is all this and much more. At its core, the BJP’s concept of progress means Indians experiencing change that enables them to fulfil their potential trigger an overall improvement in their daily lives and well-being. With this primary agenda, the party that’s armed with an incorruptible and progressive leadership aims to transform and empower the weakest and the most neglected sections of Indian society, without any biases for caste, creed or religion.” (Bharatiya Janata Party, 2014, Development section para.1)

, among other issues. To the BJP, however, development is all this and much more. At its core, the BJP’s concept of progress means Indians experiencing change that enables them to fulfil their potential trigger an overall improvement in their daily lives and well-being. With this primary agenda, the party that’s armed with an incorruptible and progressive leadership aims to transform and empower the weakest and the most neglected sections of Indian society, without any biases for caste, creed or religion.” (Bharatiya Janata Party, 2014, Development section para.1)

It is interesting to consider how in the 1920s, there was unequal access to water for the weakest and most neglected sections in society and that currently, the same issue is essentially happening. Granted, the March 2015 legislation passed was in favor those living in the informal slums, but it was due to the advocacy efforts of nongovernmental organizations. Those with political power were not looking to transform and empower the slum dwellers, contrary to their development philosophy. I think this is an example of how no change comes without challenge!

The Mumbai Port Redevelopment Plan (DP) is currently underway in an effort to develop Mumbai’s port areas into a “global city” (Voices of Mumbai Port,2015, About section para. 1). Here are some of the things the DP plans to include:

- “consolidating port activities to a 500 acre plot to the south of Mazagaon Dock

- freeing up 1300 acres to create – new mass transit corridors (enhance east-west connectivity and develop metro lines) 400 acres of green open spaces

- 300 acre entertainment zone

- giant ferris wheel on the lines of London Eye

- 500-room floating hotel

- Floating restaurants, food courts, special trade zone

- World-class cruise terminal, marinas, intra-city waterways projects and three 100 storey buildings among others” (Voices of Mumbai Port, 2015, About section para. 2).

Sure, this sounds lovely, but many people are potentially facing displacement due to the DP, significant health and environmental hazards such as shipbreaking are not addressed in the DP, and it is not ensuring that laborers will have jobs. The DP is very much economically driven and not considering the needs of the thousands of people who will be affected from this plan.

The DP reflects the BJP’s vision of turning India into a global power. The development of India is anticipated to focus on “5Ts – Talent, Trade, Tradition, Tourism and Technology” (Bharatiya Janata Party, 2014, Vision of Modi section para. 1). Recall, that their philosophy includes empowering the weakest and most marginalized groups. There clearly is some conflict for the BJP in following through on both of these aspects of what they say they stand for. It seems with regards to development, they are much more focused on the 5T’s and neglecting their commitment to the most marginalized in society. I think this will prove challenging for Yuva and the communities to navigate and it is important that public advocacy efforts outline the BJP’s contradictive messages.

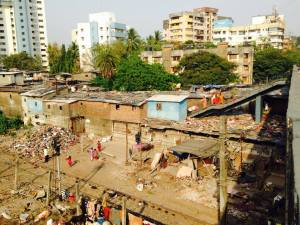

A current initiative at Yuva is the Hamara Shehar Vikas Niyojan Abhiyan Mumbai aka Our City Development Plan, Mumbai. It utilizes a participatory development approach for the city planning process and is focused on ensuring people’s rights are adequately being met (Hamara Shehar Vikas Niyojan Abhiyan, 2014). Many slum communities will face displacement because of the DP and have no alternative housing set up for them. Private businesses are looking to buy the land which these slums reside on to turn them into major roadways, according to the DP. Since it is private ownership, it is not the responsibility of these businesses to provide new housing for the displaced people. Furthermore, there are issues with accountability between the central and state government over who should provide rehabilitation to the displaced. These circumstances put the slum communities in a very vulnerable situation if they do indeed face displacement.

I have been accompanying my fellow second year MSW interns on community visits where we meet with community leaders and inform them of how the DP will be affecting them, if it is implemented as such. Since many of the slum communities are already marginalized and are often uneducated/illiterate, they are unaware of the the threat they are facing which is why it is critical that Yuva workers inform them of the DP and also inform them of their rights.

I’d like to share some of the challenges of working with these slum communities that we are facing as community mobilizers. The community leaders we have met with are appointed because they may have better resources, higher education attainment, and/or contacts with political parties. They generally are well-trusted within the communities too. Regardless, exclusivity does exist within the slums and patriarchy appears to be playing a big role too. In one community, we met with a group of leaders who identify with the BJP, the ruling political party. The leaders were all men and we faced some obstacles reaching the women. My colleague was intending to speak with some women from the community who were supposed to be at the meeting, but did not show. At the conclusion of the meeting, my colleague asked the male leaders for some contact numbers to reach the women, but was denied. Shortly thereafter, a group of women walked up to our group. The women complained that they had tried calling and calling in order to find out when the meeting was going to be held, but the male community leaders were not answering any of their phone calls. It appears the male community leaders were deliberately trying to exclude the women. This conflict certainly poses a challenge for developing collaborative work and solidarity within the community. If the women are being disempowered by the men and restricted from being agents of community change, then it will be hard to collectively fight for the rights of all individuals. I think it is certainly a strength that the women are very interested in working with Yuva, learning about the DP and their rights, and wanting to participate in change efforts.

After meeting the women, my colleagues and I went with them to a different part of the community and went over the same material which we did with the male led group. I think an important next step is to strategize how we can work collectively with the men and women in the communities. At a later meeting in the same community, there was a much larger turn out of community members, men, women, and children. It displayed that the community was being mobilized which was great, but throughout the meeting, I noticed that the women were very passively participating. They did not ask questions or stand up to talk with the workers from Yuva, contrary to their male counterparts. I inquired about this after the meeting with one of my colleagues. He told me that the community is indeed very patriarchal and that the men do not want women to actively participate in the change. I then asked what we are going to do to empower the women. The obstacle we face as the community facilitator is that we need to operate within the social norms and structure of the community. If we were to come in and start directly working with the women, it likely would not be well received by the males in the community which could ruin our efforts at working with the community at all. I am confident that as more rapport is developed with this community, we can utilize more mechanisms to promote solidarity within the community. Until then, we are ensuring that the men and women are receiving the same information and we are making sure to interview the women to gain their feedback and answer their questions about the DP.

Yuva also has been active in public protests opposing the inequitable DP in which protesters from the affected communities have been present. This is a good opportunity for all individuals from the community to learn about what it happening at a political level and also how it is affecting them. Protests are a good way to mobilize more of the community as opposed to meeting with just the community leaders. It has been really intriguing work at Yuva and especially the exposure I’m getting in the field!